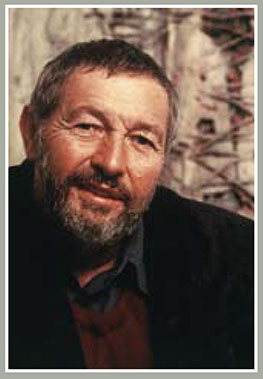

Antonín Málek

Antonín Málek’s Landscape of the Soul

It is not easy to be brief in addressing the work of Antonín Málek (1937). His corpus of work is so impressive, his path through life so intricate that an extended and ardent discourse, together with numerous interpretations, is hard to resist. Among Czech art historians who have concentrated upon Málek’s work are Mahulena Nešlehová, Hana Dobešová, Jan Kříž, Vlastimil Tetiva and Charlotta Kotíková, active in New York. Many of them have become his close friends, personally involved with his art and life.

Antonín Málek is one of the Czech artists who have left their homeland to pursue work abroad, in exile. He spent some years in Sweden and Germany, where his work merged spontaneously into local art milieus, was exhibited at a number of solo and group shows and received many prizes. How much energy does it take for a person to hold out and cope with the burden of uncertainty in exile? And how much effort does it take to maintain one’s inner continuity, so that ideas and views may be developed in a new environment with the same degree of concentration as before?

Málek left Czechoslovakia in 1968, equipped with considerable artistic and intellectual experience. His studies at the Academy of Fine Arts, Prague (1957-1963) had enabled him to contrast his work with that of other artists and provided him with a theoretical base, while an important part had been played by his friendship, dating from the late 1950’s, with the artists around Jan Koblasa. This was rooted in respect for high standards of quality in art, as well as in an affinity of style. The artists would meet in Mikuláš Medek’s studio; Málek also became acquainted with the older generation of artists (V. Boudník, J. Istler, J. Kolář) and art theoreticians (F. Šmejkal, B. Mráz, A. Hartmann, V. Linhartová, J. Kříž and D. Veselý). The group shared an interest in existentialist literature (Franz Kafka, L. Klíma, Albert Camus), Samuel Beckett’s absurd drama and modern classical and experimental music (Janáček, Martinů, Schönberg, Berg, Webern, Boulese, Stockhausen, Cage) and free jazz (Ornette Coleman, Charlie Parker, John Coltrane). His artistic experience also included participation in the non-public Confrontations shows (1960), now-legendary, that lent significant emphasis to Málek’s artistic orientation.

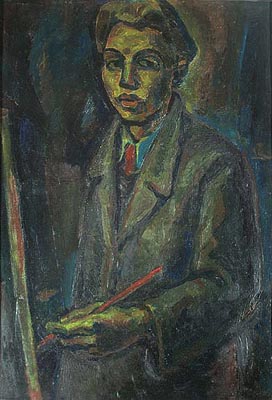

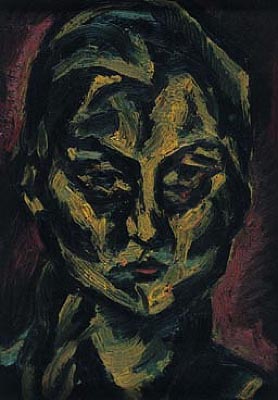

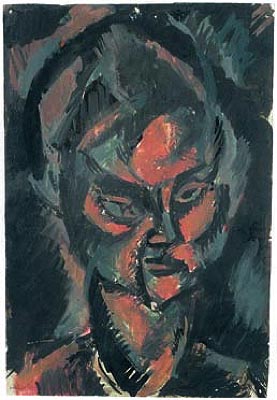

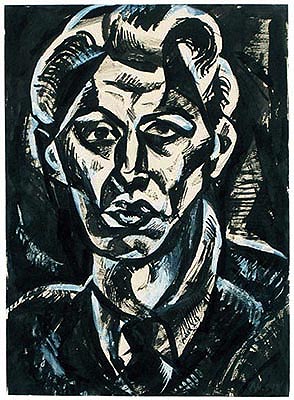

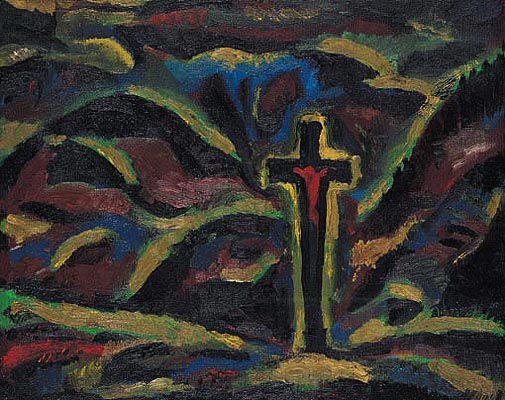

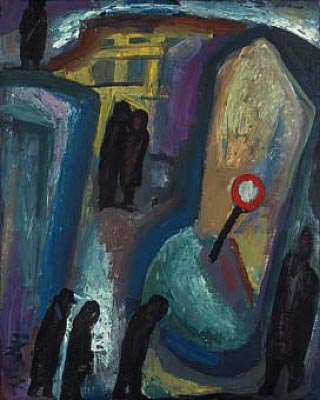

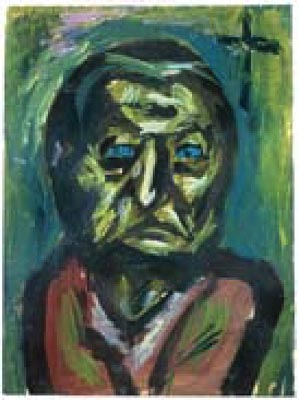

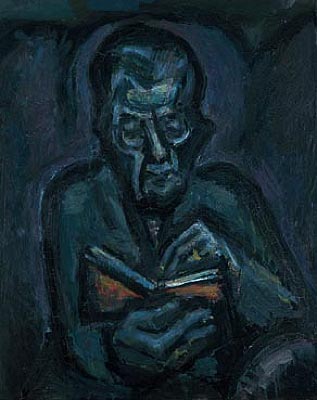

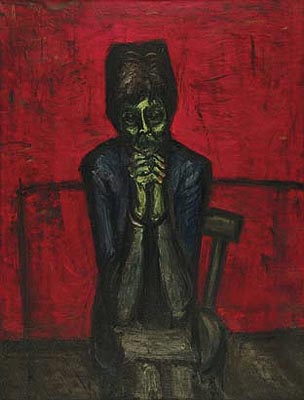

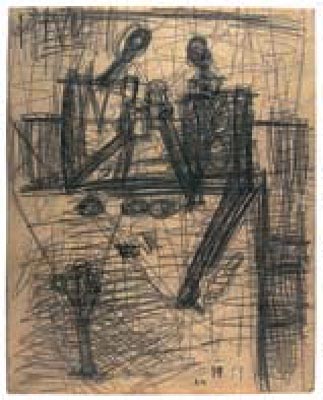

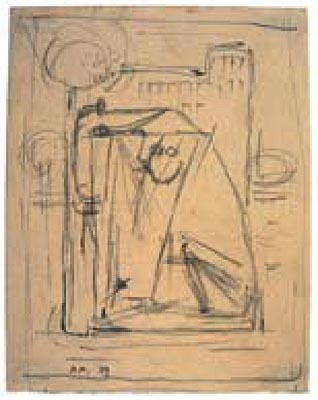

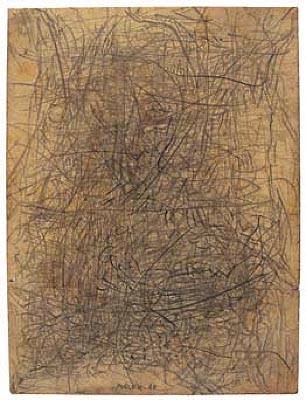

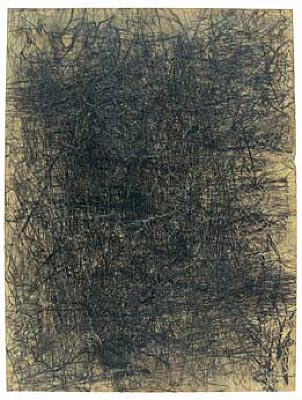

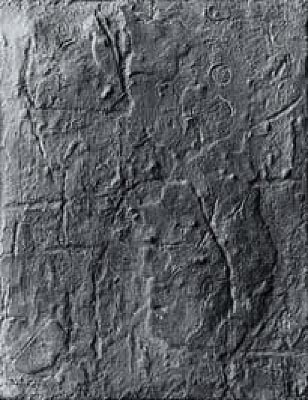

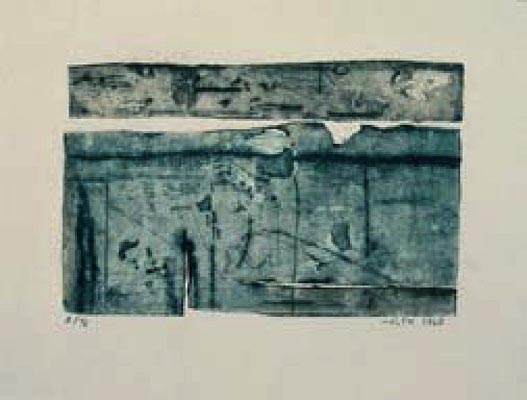

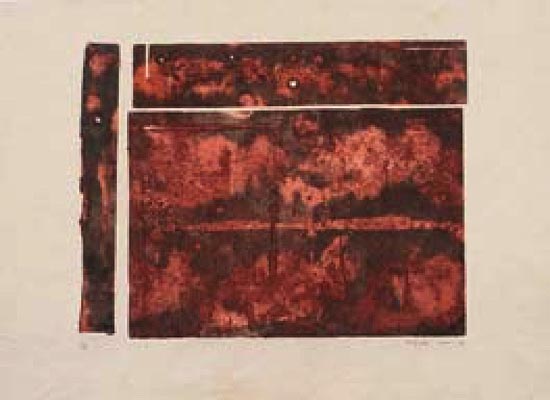

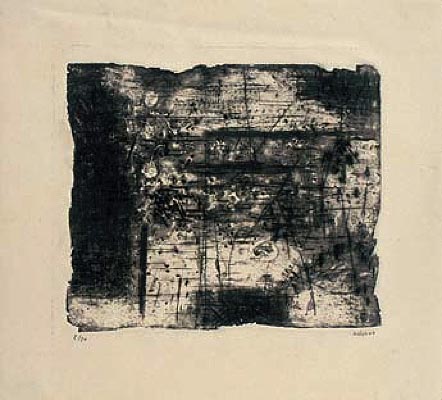

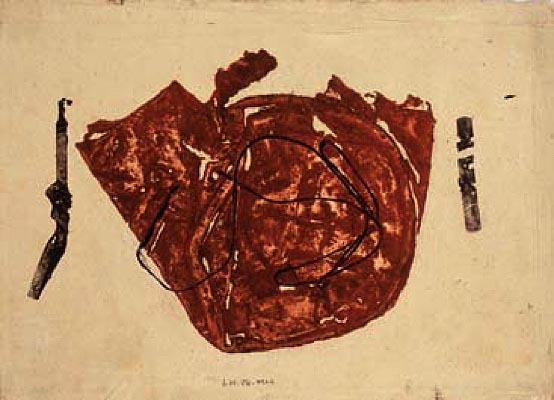

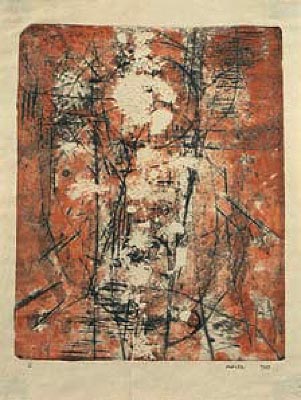

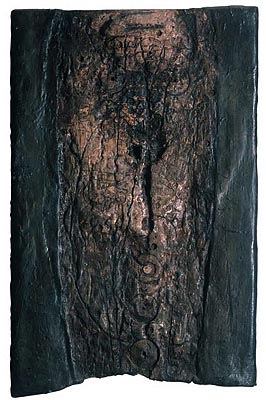

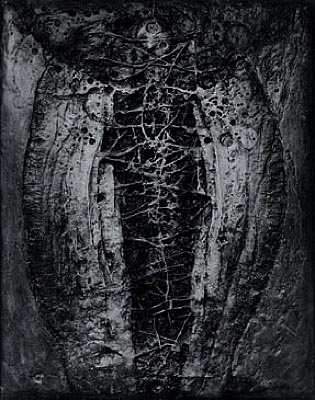

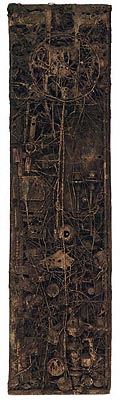

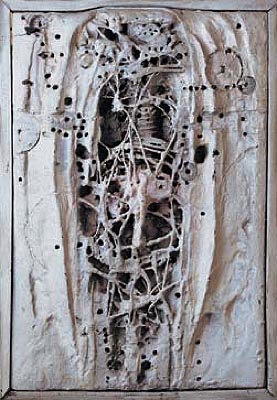

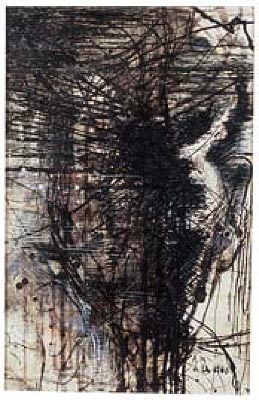

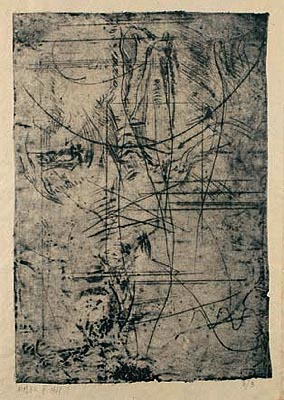

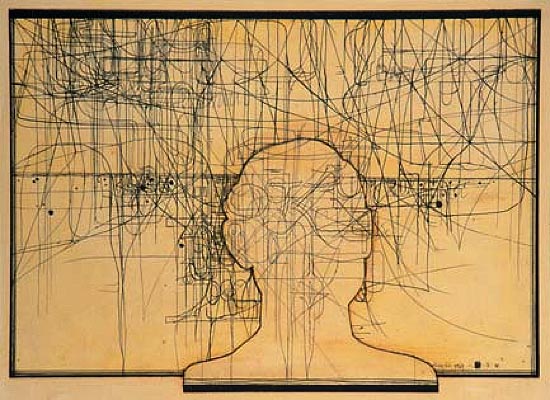

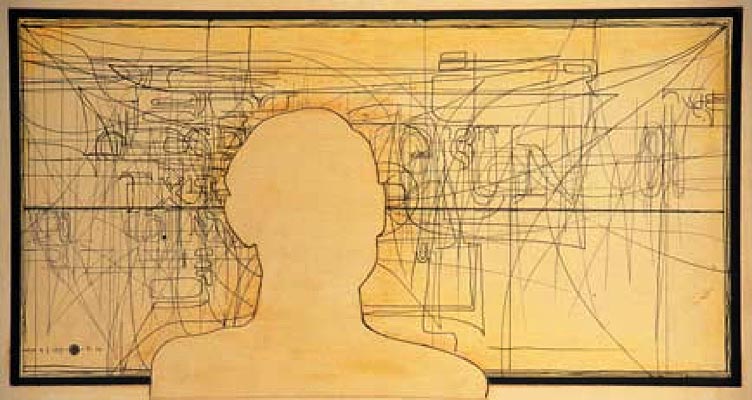

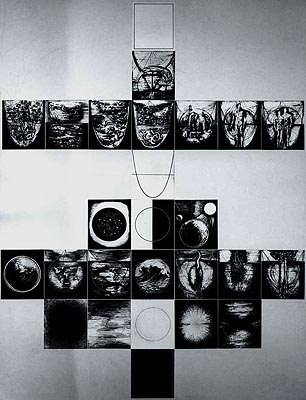

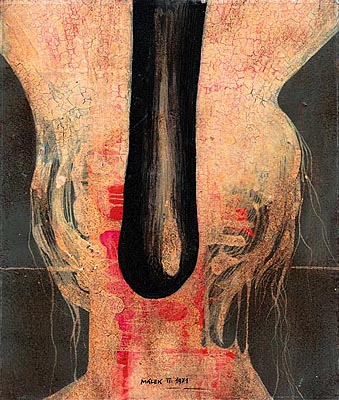

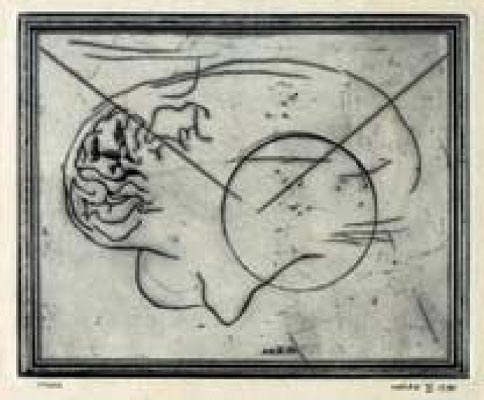

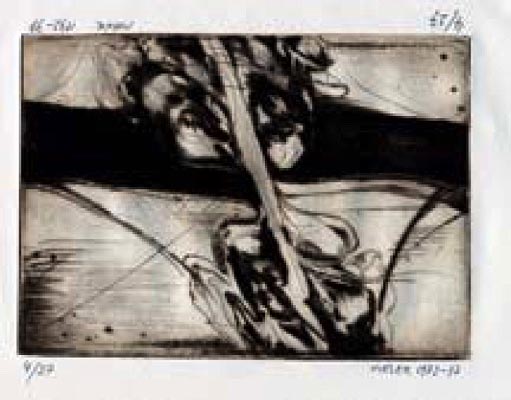

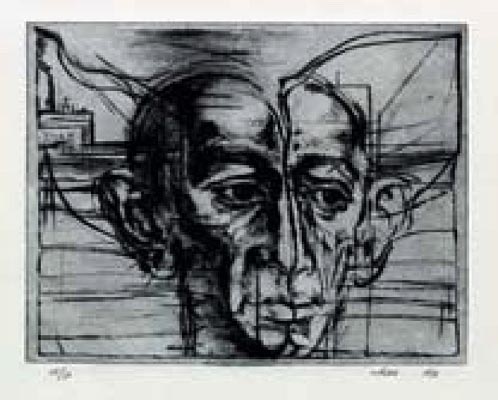

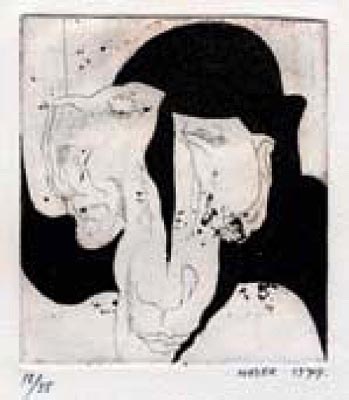

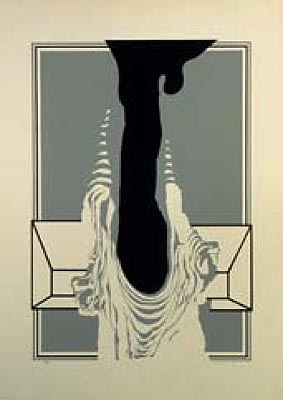

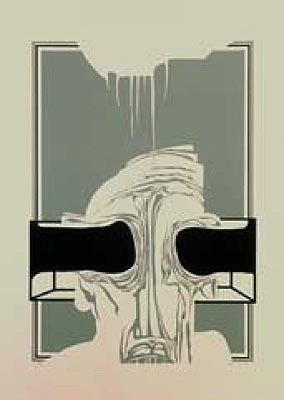

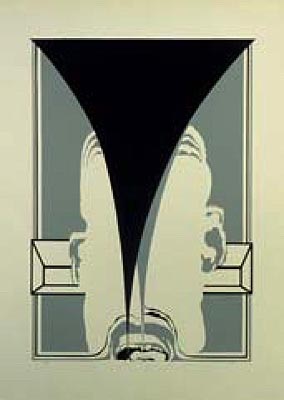

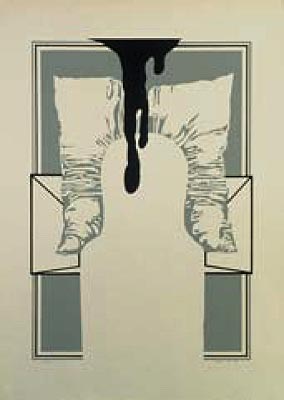

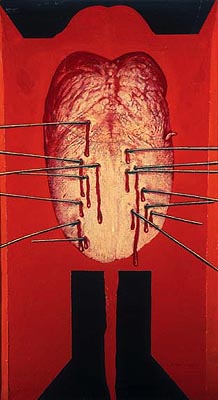

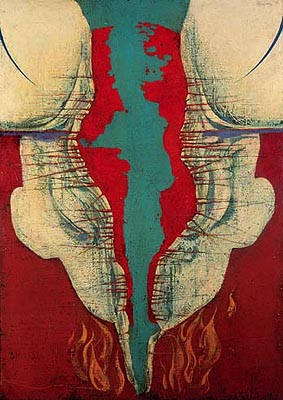

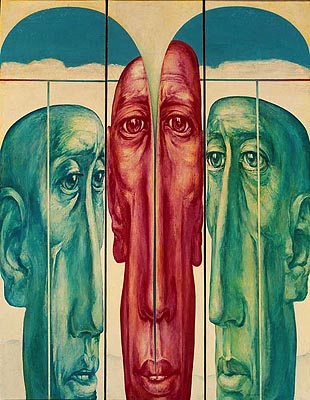

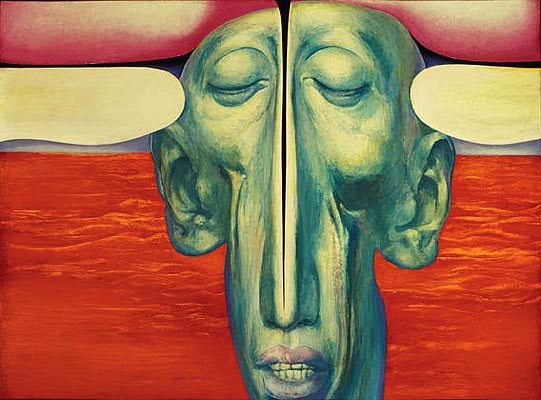

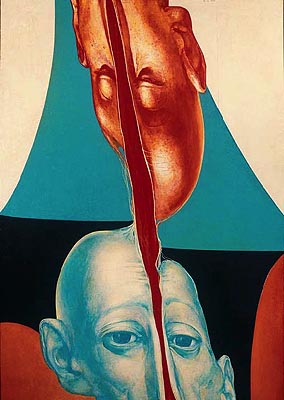

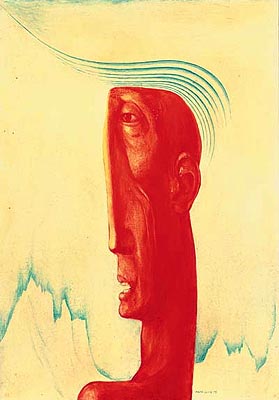

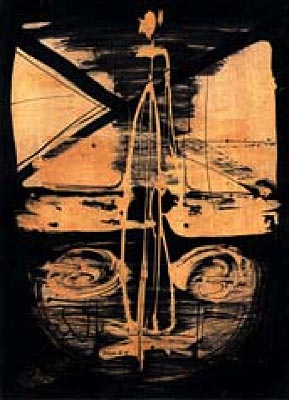

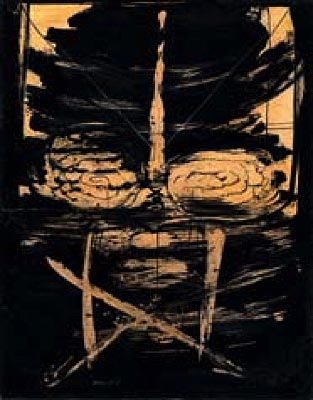

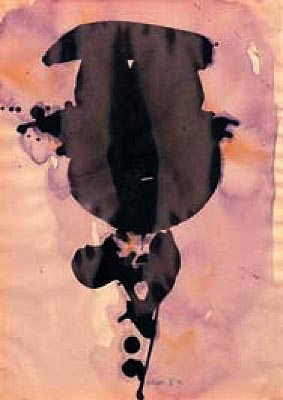

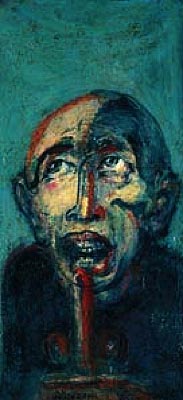

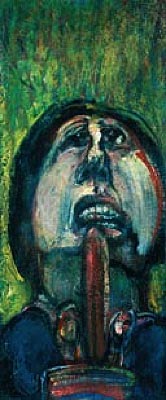

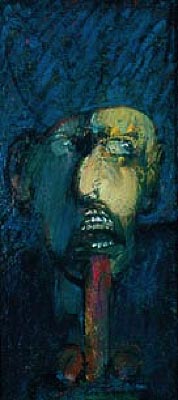

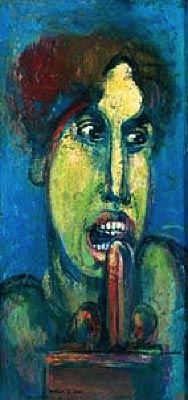

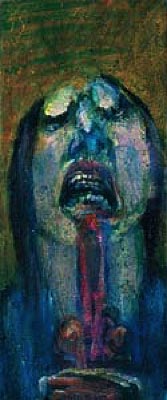

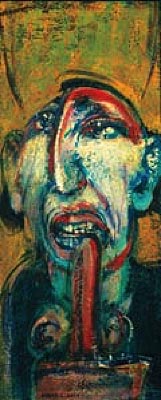

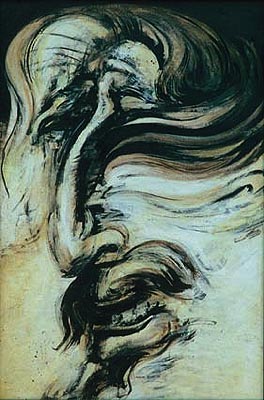

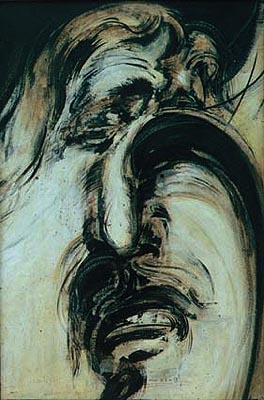

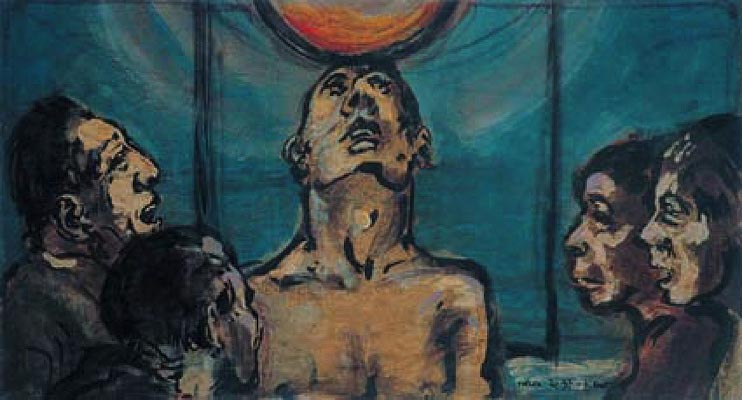

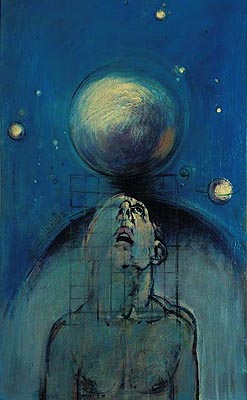

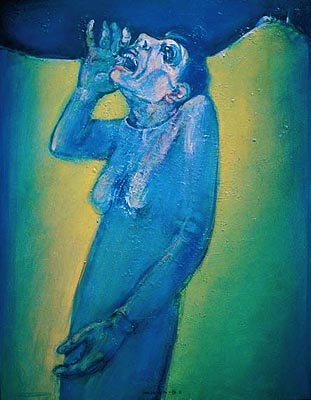

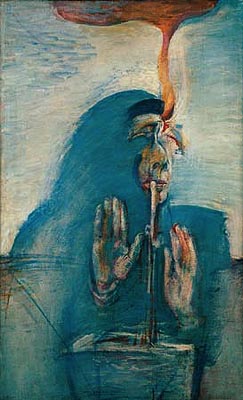

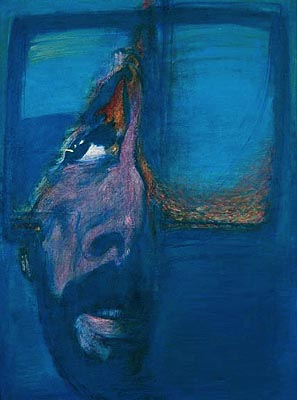

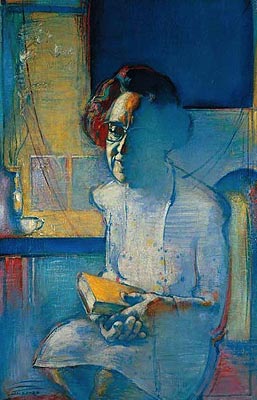

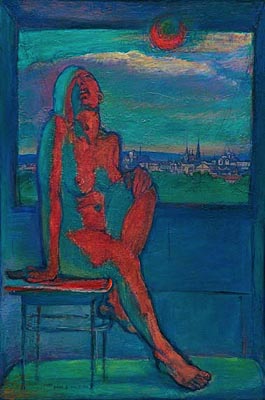

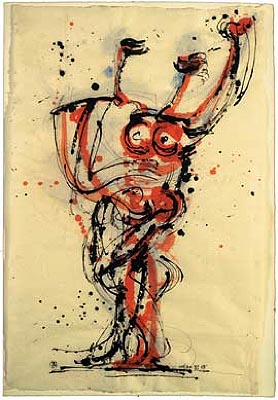

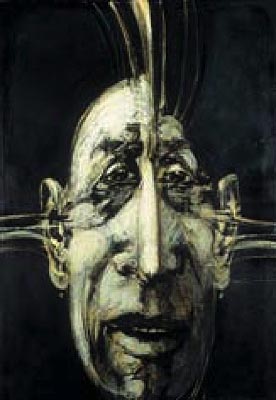

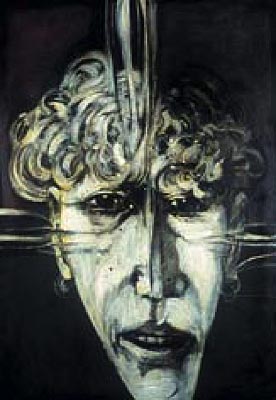

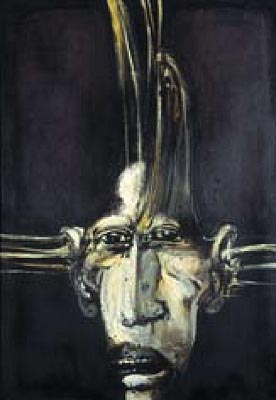

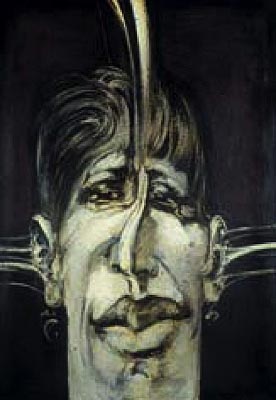

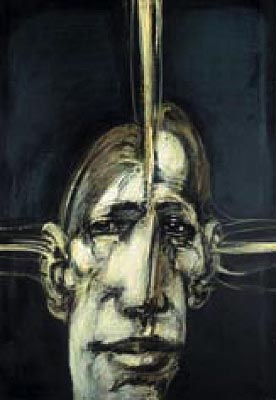

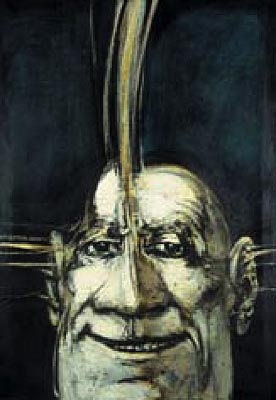

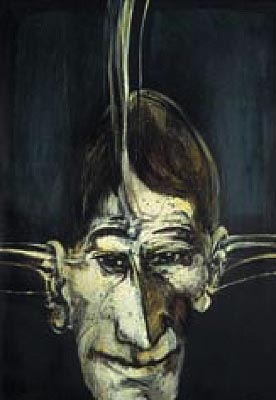

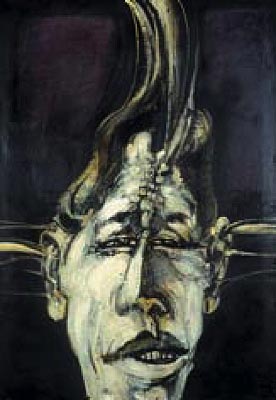

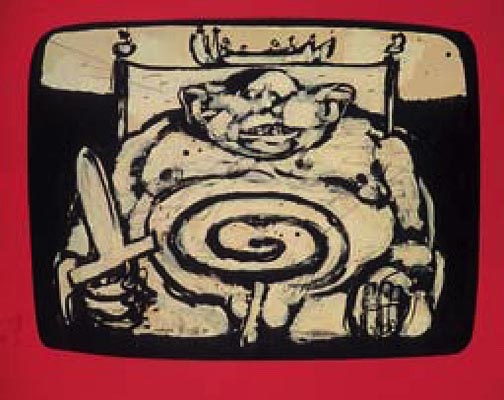

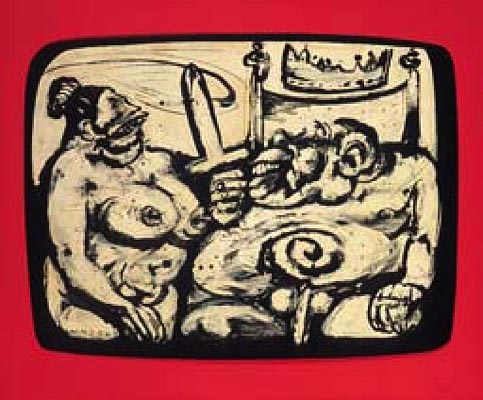

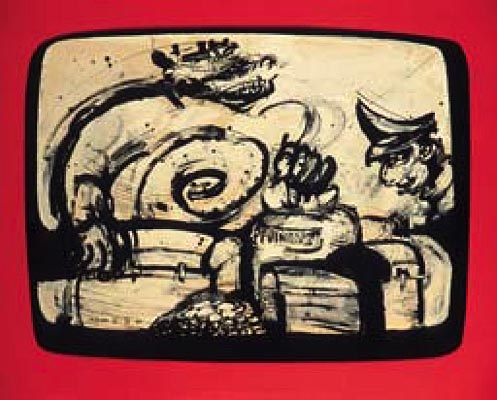

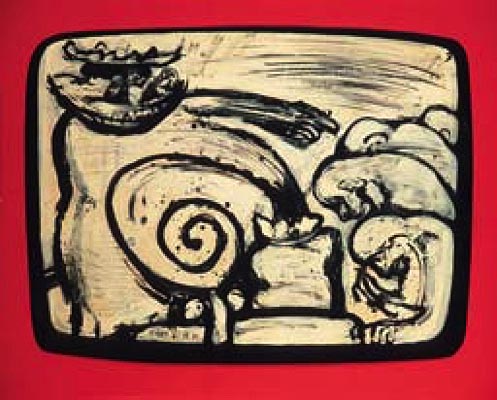

Antonín Málek’s work before emigration was thus in line with the non-mainstream (‘unofficial’) Czech art of the 1960’s, as represented by Zdeněk Beran, Eva and Čestmír Janošek, Jan Koblasa, Pavel Nešleha, Zbyšek Sion, Antonín Tomalík, Jiří Valenta, Aleš Veselý, Karel Nepraš and others, all of whom were attempting to pick up the threads of Czech art as it had been before the Second World War. In the late 1950’s an interest in the human figure and portraiture came to the forefront of Málek’s oeuvre. The figure also appeared frequently in his drawings and prints, where it was coded into hidden symbols and reductions, sometimes approached as details of the human body (eye, knee, buttocks). The figure is also present in the artist’s informel material pictures, especially the vertical ones, in which the volume is concentrated around a central slit. This scar-like element refers to more than the physical; it indicates the person as a spiritual being with a deeply hidden but vulnerable soul.

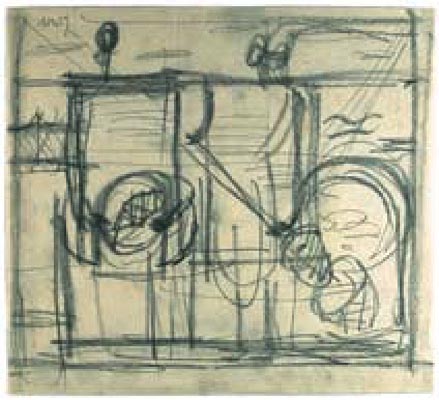

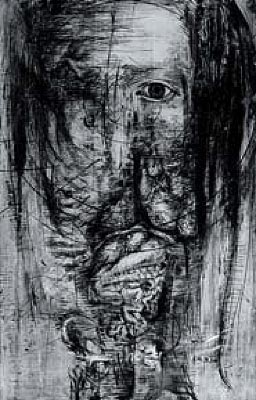

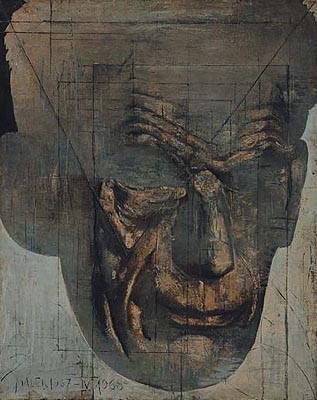

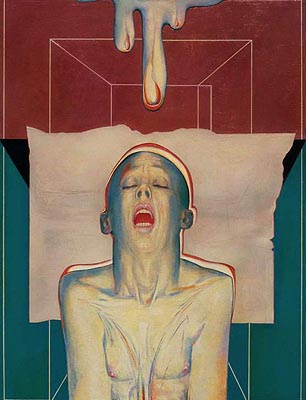

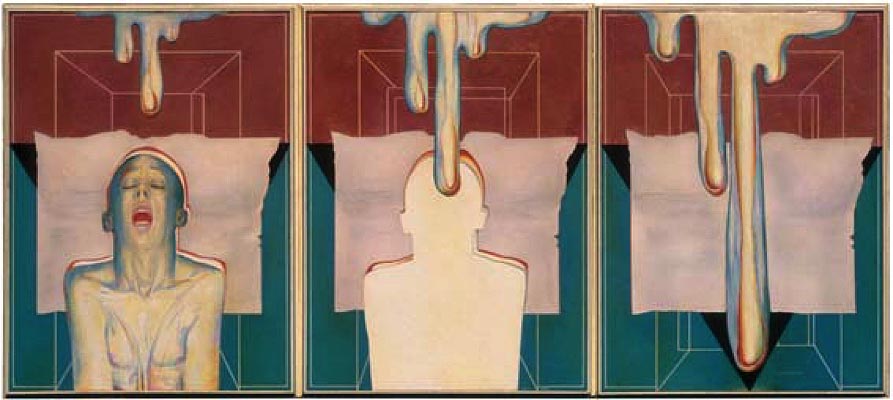

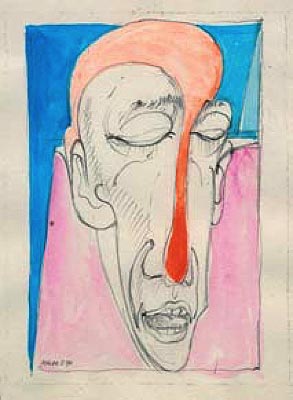

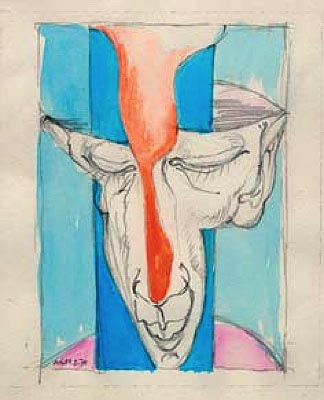

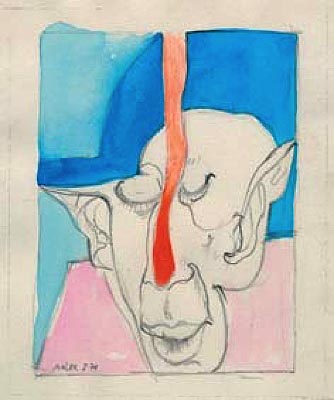

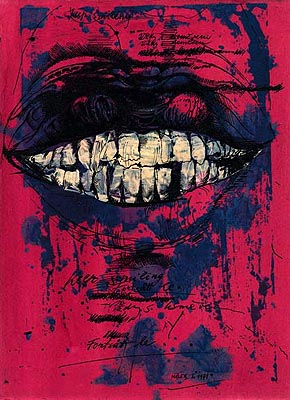

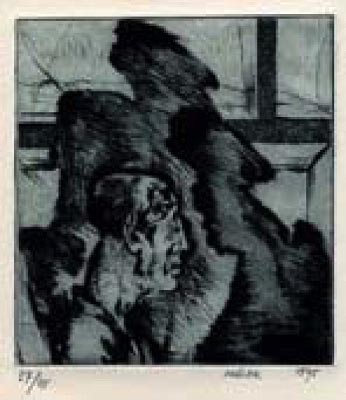

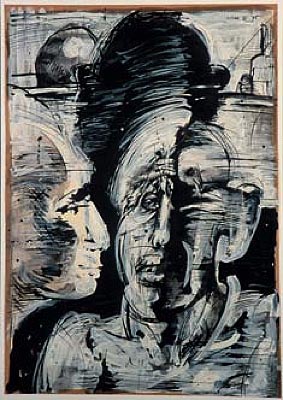

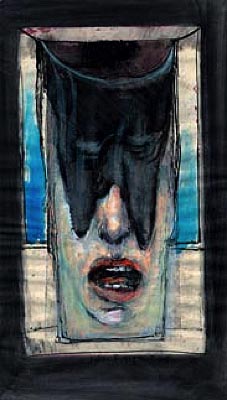

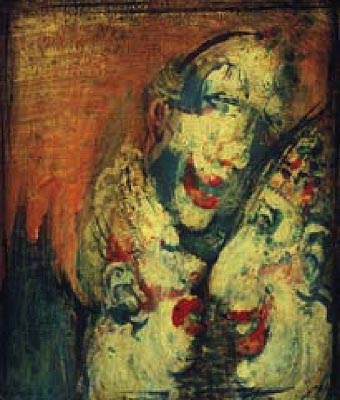

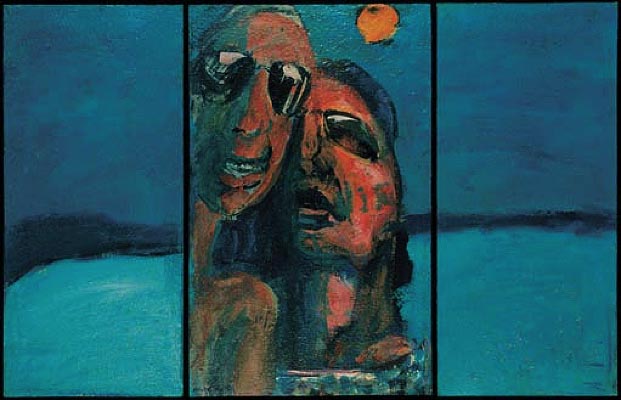

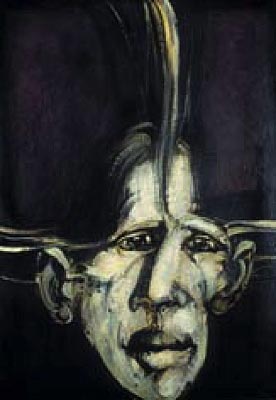

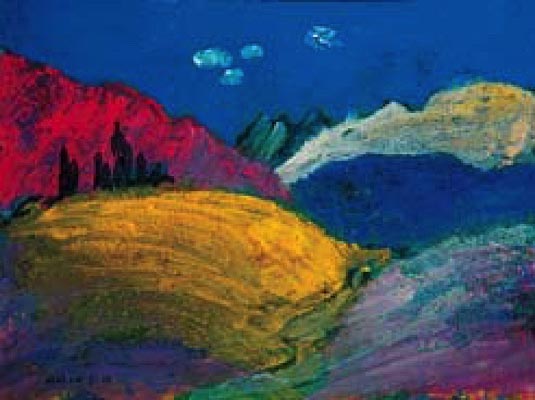

A symbolic milestone along Málek’s artistic path was his portrait of Samuel Beckett (1967/68), which brought an end to his work in his homeland and bid farewell to informel tendencies. The following years of exile in Sweden were characterized by a solidity of form and areas of clear colours that appear to have absorbed the freshness of the pure Scandinavian light and air, perhaps even freedom (Pilgrim in the Mountains, 1973; Yellow Sea, 1973). His pictures and drawings from this period also feature references to the political situation at home (In Memoriam Jan Palach, 1970; Monument to Censorship, 1970/71), as well as humour and bitter irony (Keep Smiling, 1971).

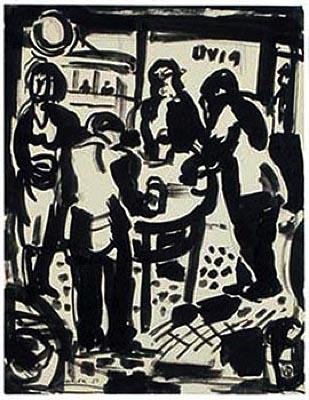

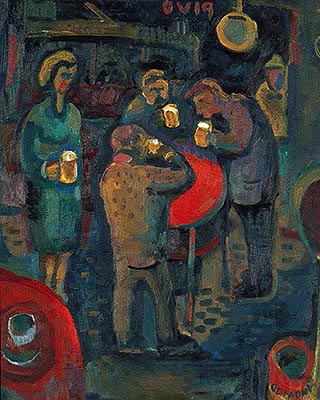

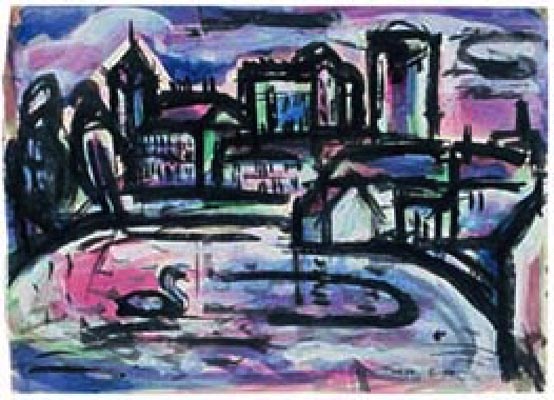

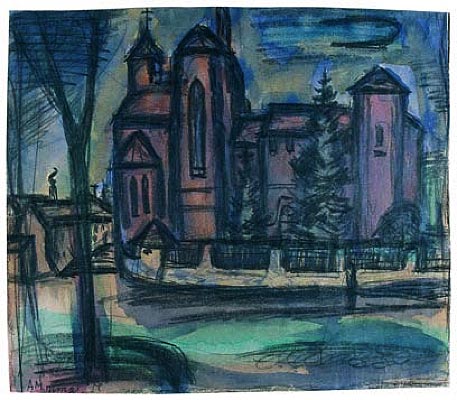

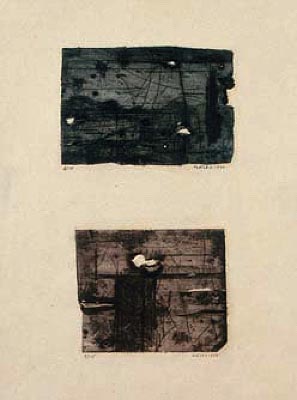

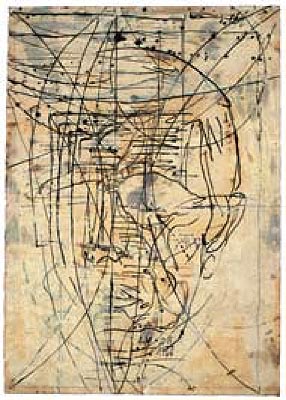

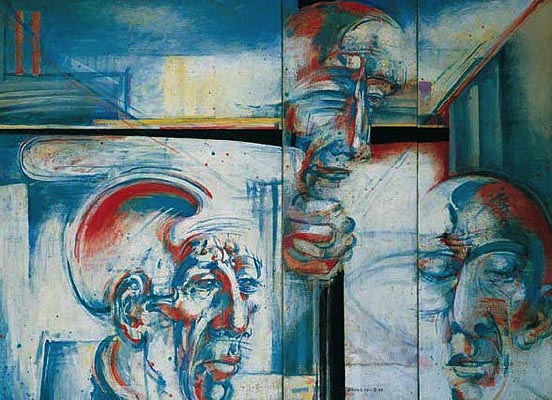

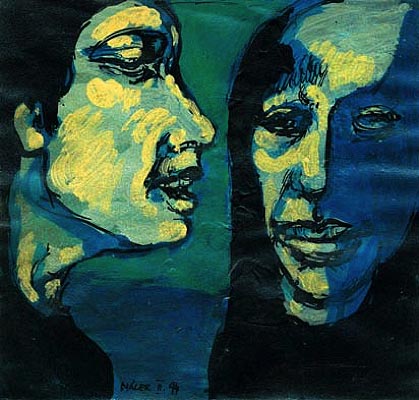

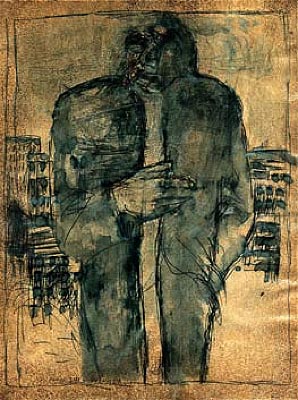

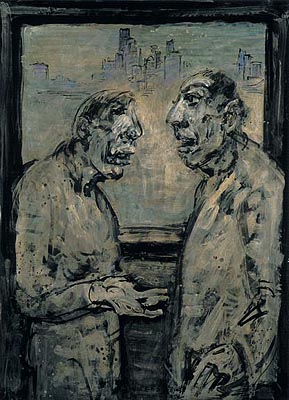

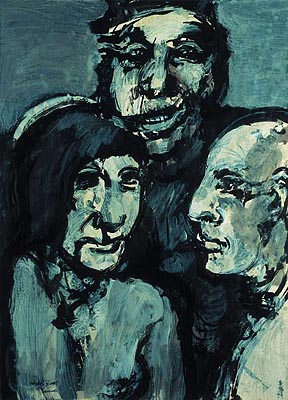

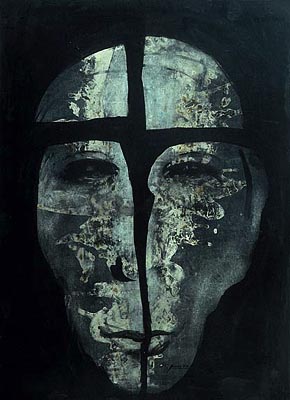

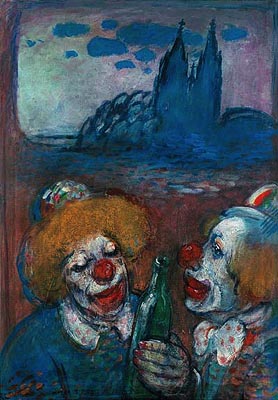

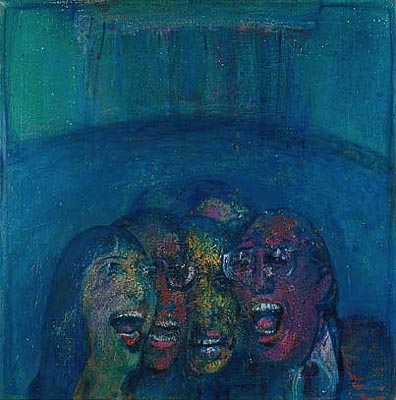

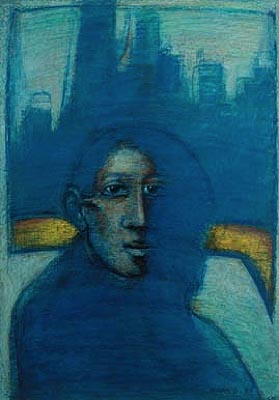

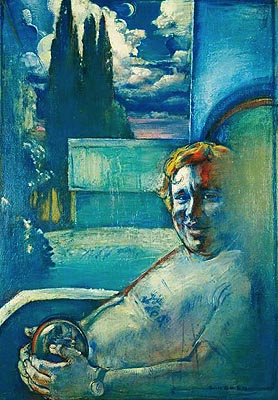

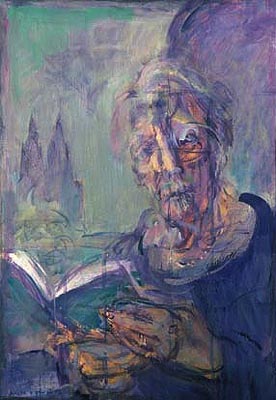

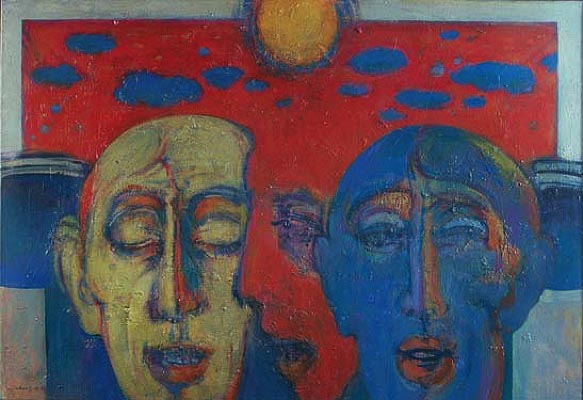

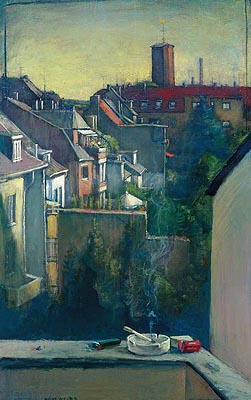

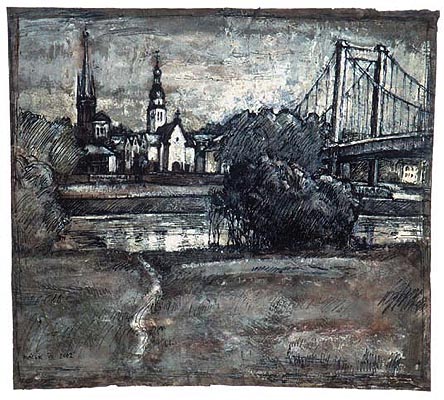

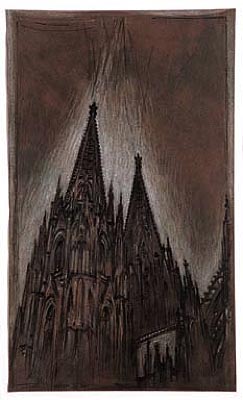

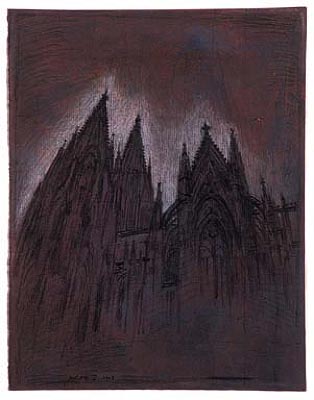

In 1973 Antonín Málek met Ulrike Málek–Lohmeyer, a sculptor and ceramic artist, who became his second wife with whom he started a studio in Kiel, Germany. They lived and worked in Alingsås in Sweden and in Kiel where they kept in touch with emigrant artists Jan Koblasa and Jiří Valenta. Málek and Lohmeyer split up in 1979 and he moved to Cologne, where he still lives. He has produced countless series of portraits, figurative drawings, paintings and prints loosely based on reality. They all hold in common relationships to the primeval essence of man, always assessed at a generally valid level (Cracked Mirror I-VI, 1979; In a Lonely Landscape, 1980/81). The human soul with its loneliness and emptiness, its desire for fulfilment and security, becomes part of the universal content of human existence in these artworks.

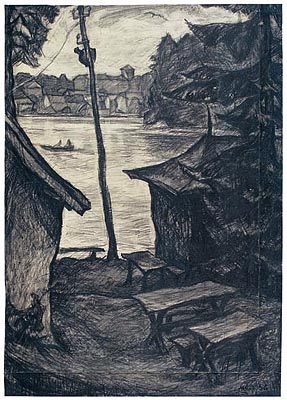

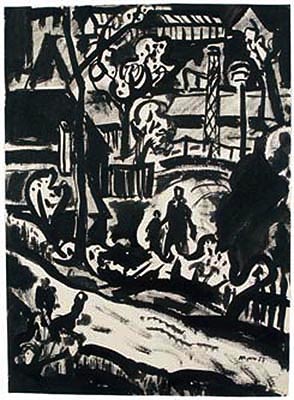

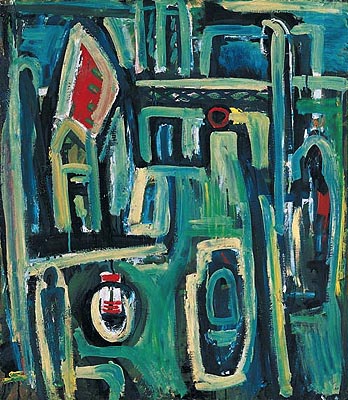

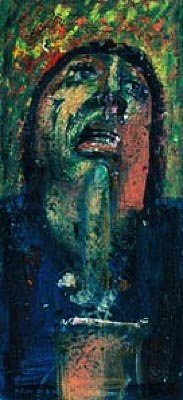

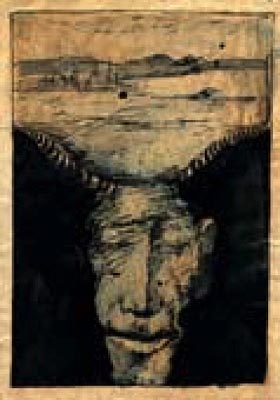

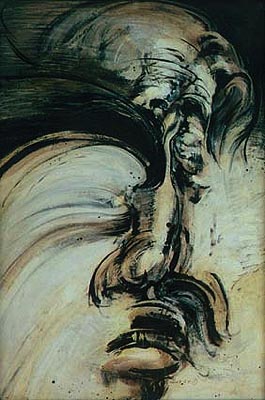

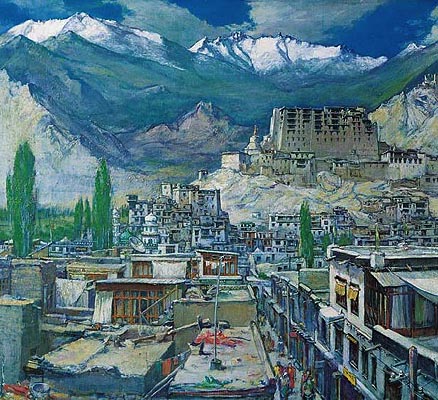

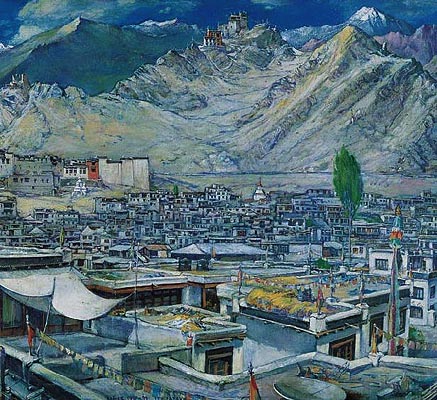

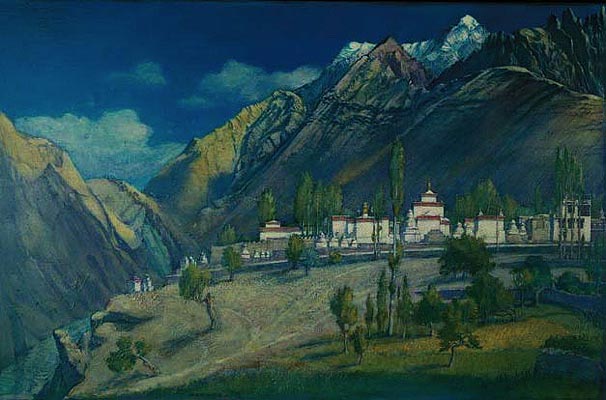

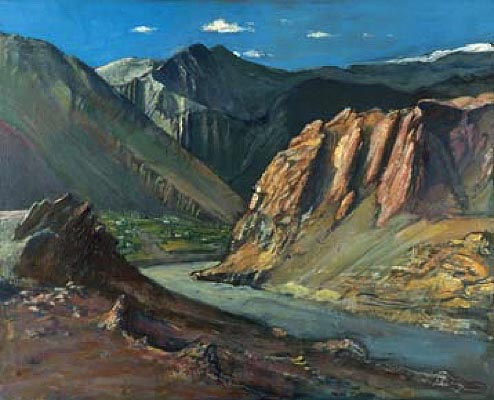

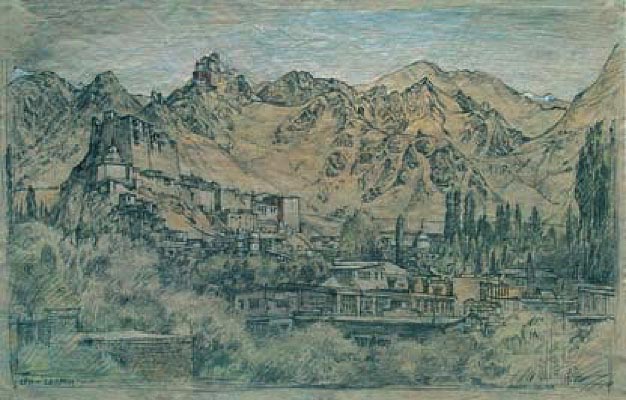

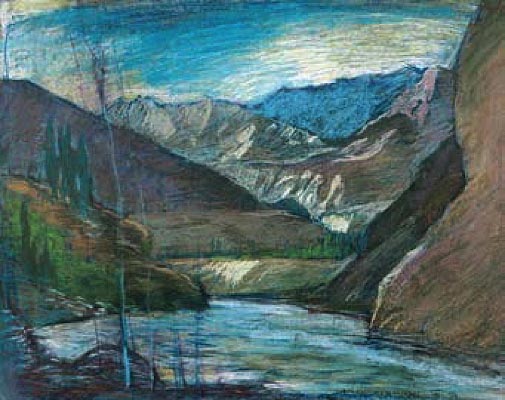

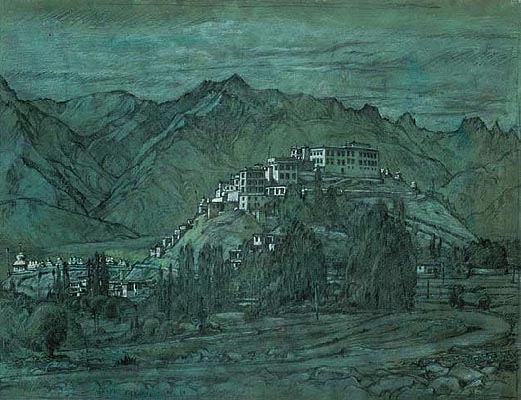

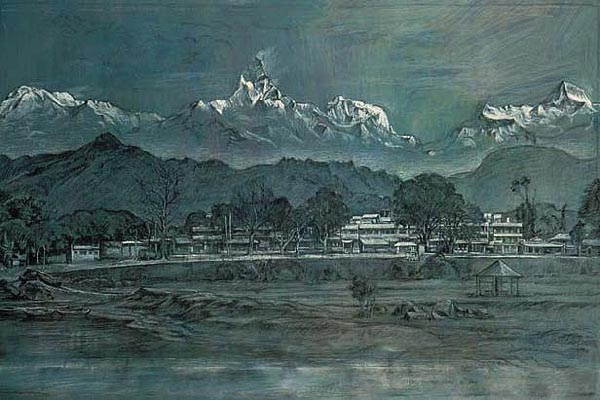

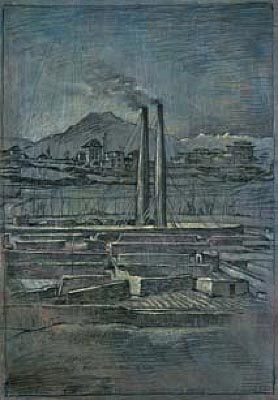

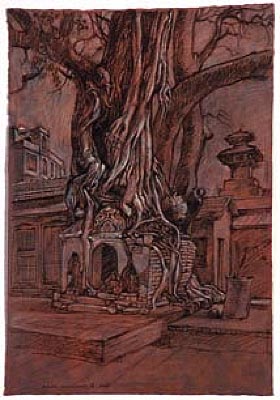

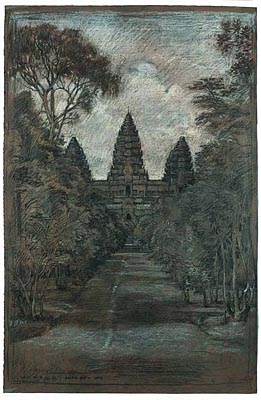

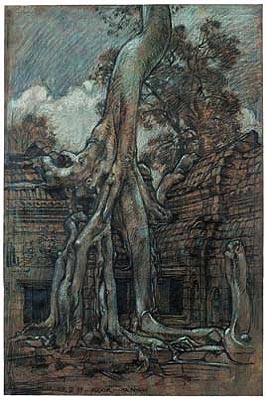

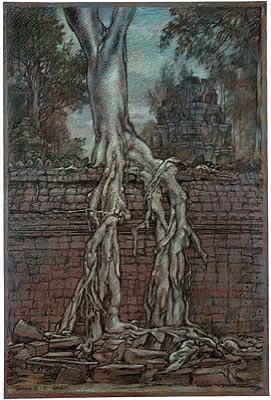

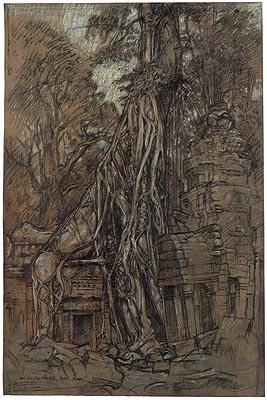

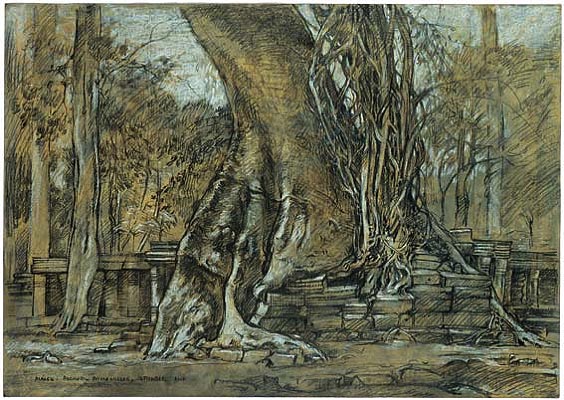

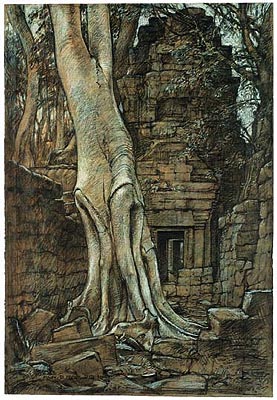

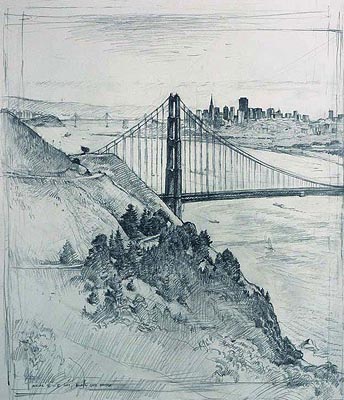

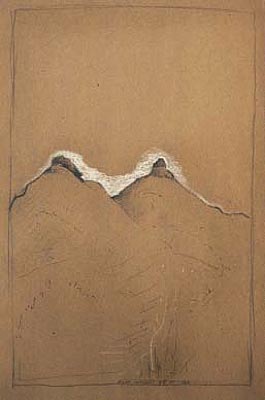

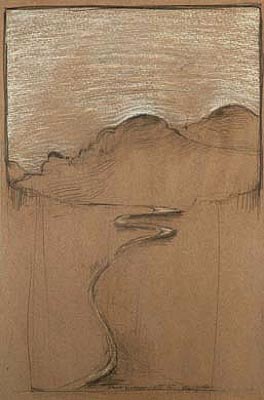

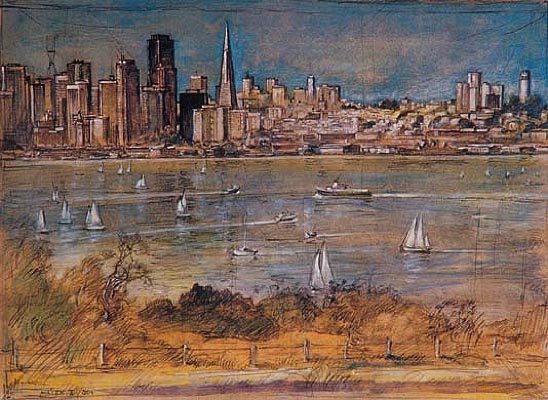

The landscapes that have had a presence in Málek’s oeuvre since 1993 also stem from this philosophical base. At this time the artist started to travel to culturally and geographically remote regions, among them Ladakh and Cambodia, where deeply-rooted traditions maintain the most basic principles of human existence. His landscape drawings and paintings, detailed yet at the same time light and rendered with virtuosity, are not “photographic” transcriptions but records of an intellectual process through which a concrete landscape Is transformed into a globally perceived reality. The circle of Málek’s art logically closes. The issue of human existence observed in figures and portraits culminates in “portraits” of landscapes viewed as images of the world, a world within the complex system of which man is anchored.